When can you base a design on your experience and when is simulation a better bet?

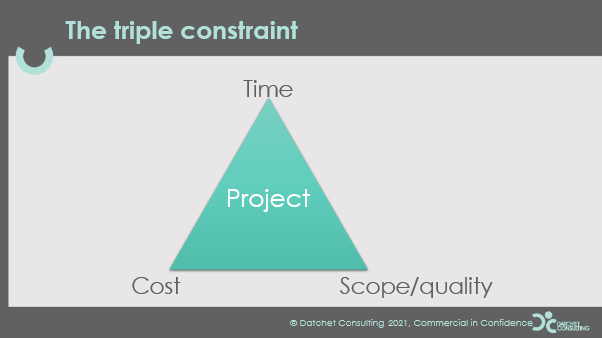

What matters in manufacturing and logistics? Figure 1 describes the Triple Constraint, which you can find in many forms, and shows how time and cost represent budgets that depend upon one another and scope of the work or the quality needed. Falling behind (scope), for instance, pushes up costs and adds delay.

Simulation offers a bonus for all three constraints: building a model is quicker and cheaper than building a factory, say, and you only have to focus on the key parts.

Figure 1. The triple constraint: time, cost, and the work to be done all depend on each other.

Figure 1. The triple constraint: time, cost, and the work to be done all depend on each other.

What do we need to know to make good decisions in design?

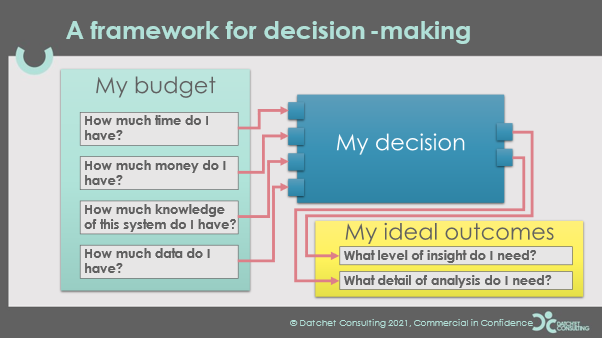

A helpful framework is to think of decisions in terms of the budgets you have and the outcomes you need as shown in Figure 2, which is based on earlier research [1].

Figure 2: Making a decision depends upon what you have and know and what you need.

Figure 2: Making a decision depends upon what you have and know and what you need.

Budgets

Figure 2 elegantly combines tangibles and intangibles – real money, for instance, and your understanding of what you know. On the whole, we are too optimistic as decision-makers and assume that key questions can be answered more quickly or cheaply than they can. We may also believe we understand what we want better than we really do, or that our legacy provides more information about our next design than it really does.

To set time and cash budgets, we must factor in the risk of failure: the bigger the step our design represents into new territory, the greater the risk. Simulation allows more failure mechanisms to be explored at the outset, so it is important to set early design budgets realistically. The more senior you are in your organization, the more responsibility you carry for getting this right, since the cost of remedial activity will also be your responsibility as well as any knock-on costs of delay in getting things running again.

Knowing what we know and how relevant it is, is a judgement call, guided by how many similar projects we have undertaken before or how much contingency we typically spend. We may also reflect on how technology or regulation has changed since the last time.

Outcomes

If optimism underestimates how long or how much is needed, it often overestimates what we know and what that is worth. Usually, we need two types of answers for projects:

- Operational answers, e.g.:

- Is this strategy better than that – and if so, how much?

- How will this design operate under shortages of staff or inventory, surges in demand, seasonal market changes, etc?

- What unintended consequences might lie in this design, and what can I do about them?

- Business issues, e.g.:

- What are the trade-offs between investment and income revenue?

- What would a year’s operations look like for each of my top layout options?

A fair assessment of our knowledge and what it is worth, along with the stage of design, will shape whether we are looking for general insight or hard figures. In the early stages, we usually want insight – is this layout better than that? – whereas in the latter stages, we usually want specific detail: for instance, is my margin likely to fall below 20% during a harsh winter when I experience extreme seasonal shifts in product and higher levels of staff sick leave?

Example

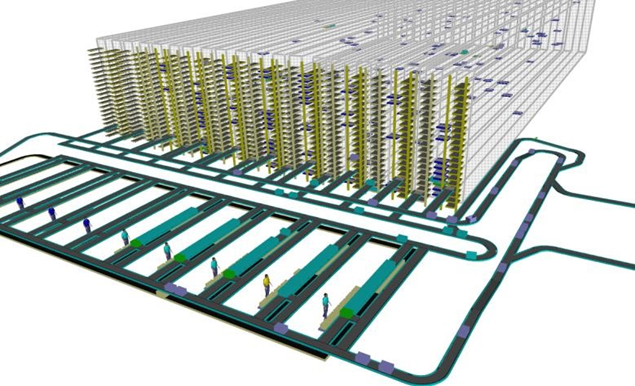

Figure 3 shows a study commissioned by Logistics Automation and Systems Technology, of Hampton, VA [2]. This is a goods-to-person (GTP) system, requiring each of the 10 people shown to be able to pick the appropriate goods efficiently from a storage facility that is 10 aisles wide and 20 levels high. It is typical of an e-Commerce fullfillment facility.

Figure 3: A simulation of goods to person picking using a multi-level shuttle

Figure 3: A simulation of goods to person picking using a multi-level shuttle

This is a dynamic challenge where ordering the priorities in fulfilment is critical to success. Putting popular products near the front is usually a good strategy, but for seasonal lines (such as clothing) the priorities themselves must be regularly reconfigured. If this facility is being added to an existing fulfilment complex, then the gateways, interfaces and other interconnections must be appropriately designed.

GTP systems are expensive in themselves and so the cost of failure is high. It takes two forms: residual inefficiencies that you live with until or unless the next major overhaul is scheduled; and problems you didn’t spot in the design phase that you have to fix immediately. As a rule of thumb, fixes in the field cost at least ten times more than fixes during design.

In this case the design study paid for itself because it increased confidence that the investment would pay for itself through more responsive customer service and lowered operating costs.

References:

[1] A. Naseer, T. Eldabi and T. Young, “RIGHT: A toolkit for selecting healthcare modelling methods,” Journal of Simulation, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 2-13, 2010.

[2] M. Hobson-Rohrer and J. Baumbach, “Simulating warehouse operations: goods to picking using a multilevel shuttle,” WinterSim 2020, 2020.